We’ve all said it, haven’t we? When someone compliments our latest handmade dress?

“Thanks, it has pockets”

It’s such a commonplace thing now, the pocket. It’s fair to say it’s something we take for granted. The pocket, however, has a much more interesting history than you may be aware of. The history of the pocket goes back thousands of years and its development brings up questions relating to gender equality. For something so practical, the pocket has been manipulated throughout history in a political way.

There is no exact date for the invention of pockets, but they have been around in some form or another for a very long time; the first incarnation of the pocket in history was found on a preserved mummy in 1991 dated between 2250 and 3105 BC. The mummy, discovered in the Ötztal Alps (from whence it got the name, Ötzi) was found with a pouch, containing useful items like a scraper, boneawl and flint flake, strapped to his belt.

The word ‘pocket’ is actually derived from the Old French word ‘pouque,’ meaning ‘pouch’. A similar version to the one found on Ötzi persisted for millennia and right through the Medieval period when they were worn by both genders, attached to the person by string.

They took on increasing significance in early modern fashion. In the 16th Century when they were worn on girdles or belts by men and women underneath clothing to keep valuables safe

By the C17th, however, the pouch became a marker of gender inequality; men’s jackets, waistcoats, and breeches had pockets sewn directly into the seams and lining of their clothing, in a similar way to how they’re sewn today. Women could only fasten a ouch to a belt under layers of skirts and petticoats. Men had freedom of movement and could access their money, keys and whatever else they carried on their person easily whereas women, even if they could carry personal items, could not readily access them in the public sphere.

The V&A describes in detail how many indispensable items could be found in women’s pockets throughout the C17th-19th. Due to the fact people often shared a bedroom and furniture, a pocket was the only private and safe place to store small personal possessions, including money, jewellery, keys, gloves, snuff boxes, even diaries. They often held everyday objects like pincushions, thimbles, and scissors, not to mention the “Objects of Vanity” like mirrors, combs, and perfume. With the birth of the Industrial Revolution there were even more things for women to carry; one might well muse that this is where the need for the handbag was born.

Into the 1790s and with the beginning of the French Revolution, women’s fashion started to change; pockets were banned from women’s garments. Of course, any changes in fashion were still dictated by men; women’s clothes changed from layers intended to obscure the woman’s nether region from the gaze of men (with the bust visible for the pleasure of male viewers. led to the advantage of any and all male viewers. The female silhouette changed dramatically; instead of layers of petticoats and stiff skirts, the empire waistline was introduced – think Bridgerton – and sheer fabrics were used to create a columnal silhouette, obscuring the natural waist. There was no longer a place to hide pockets under skirts. Women began using ‘reticules’ (small, handheld bags), the predecessor to modern-day handbags. Pockets would have held so much more than these bags so this was a loss. The idea was to ensure women could not conceal anything.

Reticules were purposefully designed to be small because it was generally considered that women had no need to carry anything of consequence that allowed any form of independence; it became a symbol of a leisurely life, a ‘kept’ woman.

From the mid C19th, dresses gained fullness again, allowing for a pocket might be sewn into the front side seam. These pockets were humble in size, unable to hold much more than a handkerchief. Dressmakers and home sewists would discreetly stitch pockets into their dresses (this reminds me of a wonderful novel I reviewed on my blog).

With the turn of the 20th century and women protesting for independence, the pocket once against took on a new political vitality as a symbol of long denied independence. Instruction manuals on how to sew pockets into clothes gained popularity with women. In 1891, the Rational Dress Society had been established in London to lobby against corsets and other restrictive clothing and push for more comfortable and utilitarian options for women.

A 1910 ‘Suffragette suit’ emerged, sporting several pockets, some of which were accessible and visible.

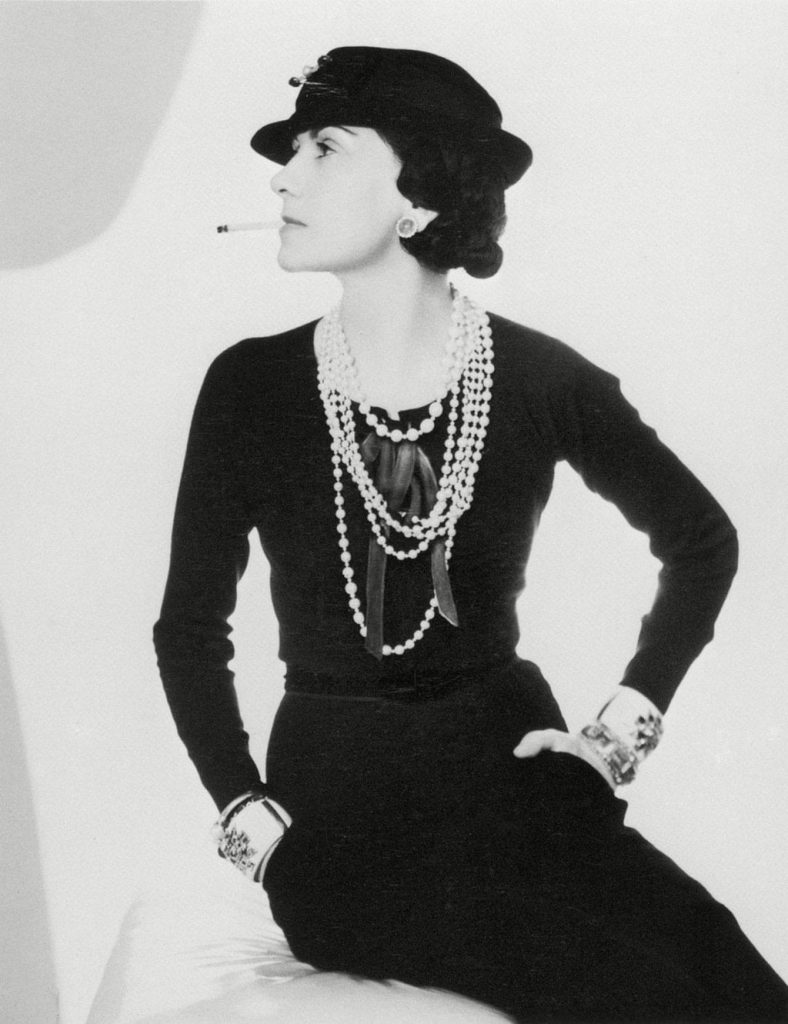

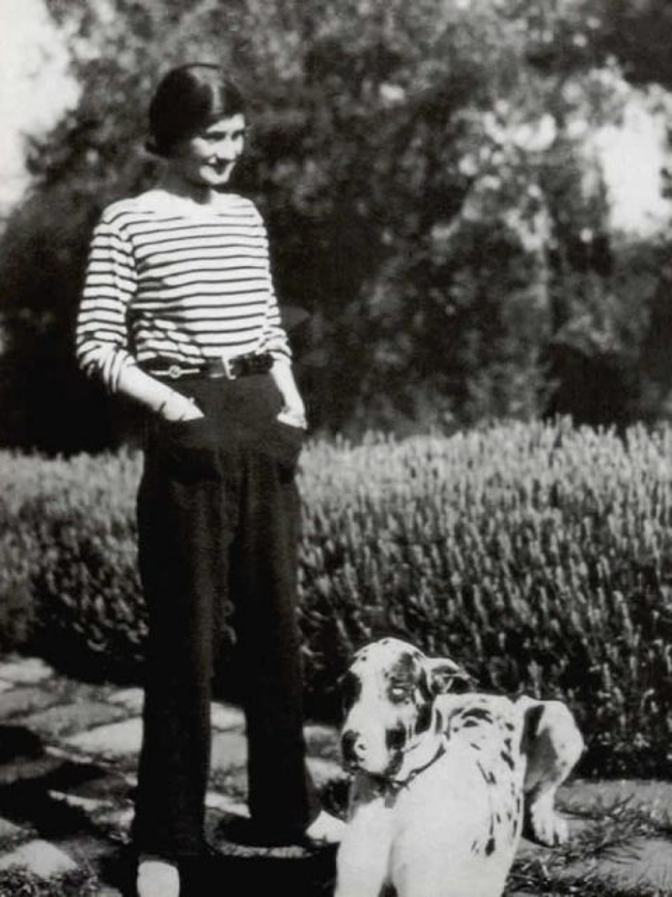

With WWI, women clothes were becoming more practical and large pockets became the norm. It was a time of unprecedented change; fashion and life changed because women were in positions traditionally held by men. They were pushing for social change and the right to vote. They found themselves in employment previously not available to them. The long skirts of the Victorian and Edwardian era were being replaced with a slimmer and more practical silhouette. With men at war, women could have their day – and pockets. Coco Chanel fed this liberation with her jersey garments and love of pockets.

Chanel’s style brought a new posture; a sort of slouch which made the wearer look relaxed and confident in a way men were well versed in.

As men returned from the war – and men were ‘entitled’ to the jobs which women had taken responsibility for – women were forced to readjust to the re-establishment of pre-War order. Men were uncomfortable seeing women in the clothes that had liberated them and so marked the return of more ‘feminine silhouettes’; in other words, slim garments that could not accommodate pockets.

The attitude to women and pockets in the mid-C20th is probably most pronounced in the words of Christian Dior: “Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration.” It’s quite an essentialist statement, isn’t it? Could the gender polarity be more pronounced? Men’s garments are created with utility in mind, while women’s garments only have pockets for decoration. It’s blatant sexism in action.

This sexism continued in the fashion industry with the birth of the handbag. With the handbag, pockets were deemed unnecessary for women. This is the industry all over, really; convincing us we need that ‘latest’ accessory. An entire industry was born out of denying women pockets. To bolster the handbag industry, women were told pockets interfered with the female silhouette, making hips wider and too lumpy. Men promoting their own viewpoint on what a woman should look like… and who reaped the monetary profit?

Pockets in garments have never lost their appeal for good reasons; they provide comfort and security. As something internal (and ofttimes secret), it is a very different entity to a handbag which can be lost or stolen, leaving a person feeling bereft and vulnerable. When a handbag is lost or stolen, you lose everything in it, too. It’s happened to me once; it is a gut wrenching feeling that leaves you feeling insecure for a long time after. While pockets are not the perfect answer – hello, pickpockets – you can feel more secure knowing they are on your person. There is a form of freedom in having your personal things close.

I think that’s one of the things I will never underrate when I sew my own clothes; that I can sew in pockets. I am sure not everyone cares about pockets in their garments but I, personally, love them – maybe partially because of the historical meaning that comes along with them. It’s having the choice, I think, that is empowering (much like Wendy in A.C. Wise’s recent novel Wendy, Darling – honestly, read it). Freedom lies in the ability to make choices.

I have always said that sewing is an act of liberation; sewing matters. Making your own garments give you agency; the ability to express your individuality and transcend the dictates of what society deems to be fashionable.